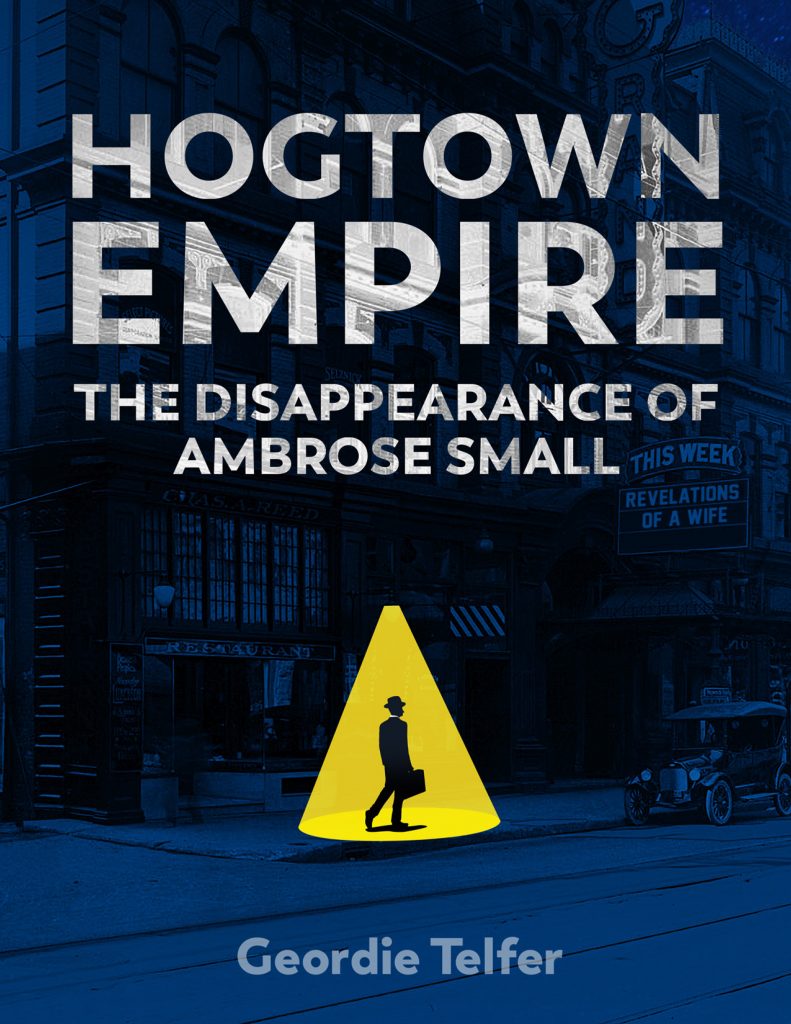

Most of my print work is long-form non-fiction. I like writing books and I’m good at it. If you’re viewing this on a tablet you can tap the paragraphs to scroll the text. Just tap to the right to scroll the page overall. Happy reading.

PROLOGUE

Eighty-mile-an-hour winds smashed through Toronto like a wrecking ball. Telephone and telegraph poles snapped. Trees uprooted. Brick chimneys toppled. Windows too many to count shattered. The storm peeled the rooftops off thousands of homes like the lids off sardine tins. Stone and metal cornice work from buildings crashed down into the streets below. On King Street a waist-high, 30-foot long chunk of stone and brick detached from an apartment rooftop and landed like a bomb in the street. At the foot of Spadina Avenue, the plant of the Gall Lumber Company was destroyed, with miles of boards splintered into toothpicks. The roof of the grandstand at the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) blew off and sailed for 50 yards where it landed in a heap of useless rubble. The CNE’s towering wooden rollercoaster didn’t simply blow over; the entire structure skidded along the ground and out into the midway – then it blew over. The flagstaff at City Hall snapped in half and crashed to the ground.

Hogtown had fallen.

The morning of Sunday, November 30, 1919, dawned on streets filled with debris. All across the city previously well-appointed thoroughfares were now jumbles of smashed stone, wooden beams and fencing, fallen business signs, crazily skewed poles, gravel, tar paper, innumerable shards of razor-sharp glass, and tree branches everywhere. A large, falling tree branch claimed the life of the storm’s sole victim, though numerous injuries were reported. Then there were the contents of the houses that had burst open: papers, clothes, and other small items were strewn about all over the place.

Dazed citizenry emerged and began walking wherever it was they were going, probably church since it was Sunday, after all. Many drivers found themselves pedestrians by necessity, their conveyances having been destroyed by falling debris. Their faces wore an expression named during the recently ended Great War – shellshock. The city’s streetcar system sagged in tatters and the streets were impassable. Snapped Hydro poles swung back and forth, hanging from electrical wires. Churches, businesses, homes, infrastructure; none had escaped the storm’s wrath. The papers noted that Toronto’s theatres and movie houses had all gone dark.

This was the scene that presaged Ambrose Small’s disappearance. As Sunday’s dusk lowered over the shattered city, the principle actors were waiting in the wings. In Montreal, financier William J. Shaughnessy was boarding a train to Toronto, bearing with him a cheque for $1 million. London, Ontario, lawyer E.W.M. Flock was pleased; after months of wrangling, his clients Ambrose and Theresa Small were selling their chain of theatrical holdings for $2 million, starting with a $1-million down payment.

The next day, Monday, December 1, all of these players gathered in a Toronto bank office. Papers were signed. The cheque was handed over. Hearty congratulations were given. Someone lightheartedly joked to Theresa Small that she was probably the first person to walk up Yonge Street carrying a cheque for $1 million. And with that, the players took their bows and went their separate ways.

Outside, among ruined homes and rubble-strewn streets, Toronto was discovering the extent of the destruction. Because the day after the storm had been a Sunday, no newspapers were published. This morning, on their first day back, the papers were a litany of carnage and strange events. As Ambrose Small’s fortunes reached their zenith – and their end – in a boardroom on Yonge Street, regular Torontonians were reading about a weird blue light seen above Lake Ontario during the storm. With both of the city’s power services knocked out, Hogtown had been in complete darkness. Then, shortly after 8 p.m, observers on high ground in the east had watched an odd spectacle unfold. Through the thick blowing snow, out over the roiling lake, an icy sapphire of light punctured the darkness. It resembled a blue flare on a ship in distress, but the light didn’t behave like a flare. It hung low in the sky and trembled. Then there was a “blue flame of great intensity which lit up the whole southern section of the city. This flare was repeated several times during the storm. It was too slow and too blue for lightning …”

Ambrose Small was, by no stretch of the imagination, “a man of the theatre.” It’s doubtful that he knew stage right from stage left. But his single-minded drive for profit and dominance laid the foundation for professional theatre in Ontario. His theatre chain had a reputation as the most carefully booked circuit in North America. Small presented a shrewd balance of crowd-pleasing musicals, melodramas, and family entertainments, mixed with enough highbrow “thee-ah-tuh” to keep his audiences happy. For the more refined of his clientele, the wild weather of Saturday night might have brought to mind these lines from Julius Caesar.

I have seen the tempests, when the scolding winds

Have rived the knotty oaks, and I have seen

The ambitious ocean swell and rage and foam,

To be exalted with the threatening clouds:

But never till to-night, never till now,

Did I go through a tempest dropping fire.

These are the words of Caesar himself, who is shaken after witnessing disturbing omens. He wonders if they augur forthcoming events and whether they bode well or ill for his future.

What better prologue for a theatrical titan about to depart?

NED & MARGARET JORDAN

“Many a good hanging prevents a bad marriage.”

– William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night

Off the Coast of Nova Scotia

(September 13, 1809)

Stairs wiped the stinging gunpowder off his face and turned to his sea chest where he kept a brace of pistols. He flipped it open only to discover that both guns were gone. Had Ned Jordan taken them? There was no time for wondering- he needed some sort of weapon, if not a gun then at least a blade. Captain Stairs rooted around in the trunk for his cutlass, but it was gone too. Then he heard four or five pistol shots ring out from above. Armed or not, Stairs knew he had to get up on deck to find out what the devil was going on. He started up the ladder but met Ned Jordan coming down.

Captain Stairs describes the encounter in his own words: “On going up the ladder I met Edward Jordan, in the act of descending; one of his feet was on the ladder; he held an axe in his right hand, and a pistol in his left. I seized his arms, and, begging him for God’s sake to spare my life, shoved him backwards, when he snapped the pistol; I instantly grasped it by the muzzle, wrested it from him, and threw it overboard; and called Kelly the mate to my assistance, but he made me no answer. Benjamin Matthews came hastily aft, he appeared to be wounded, and fell down. By this time I had taken the axe from Jordan, and endeavoured to strike him, but he held me so forcibly as to prevent me. I, however, threw the axe overboard.”

At this point Captain Stairs had managed to disarm Ned Jordan, but he hadn’t counted on Ned’s wife, Margaret, who suddenly appeared, shrieking like a banshee and brandishing a boathook.

“It is Kelly you want,” she screamed, “Ill give you Kelly.” Then she set about hitting Stairs with the handle of the boathook. Between blows from Margaret Jordan, Stairs had managed to notice three very disturbing things: First, seaman Benjamin Matthews lay where he had fallen, showing no signs of life-this would explain the pistol shots he had heard earlier. Second, the wounded seaman Heath had somehow managed to come up from below, but now he too lay lifeless on the starboard side of the deck. Third, his first mate, John Kelly, was not even trying to help him. What was going on here?

Disentangling himself from the Jordans at last. Stairs watched as Ned Jordan stalked to the stern of the ship and picked up another axe. Then Jordan walked over to where Matthews lay unconscious and struck him several gory blows in the back of the head with the business end of the axe.

Through this entire ordeal, Captain Stairs seems to have remained remarkably clear-headed. Realizing that the Jordans were going to kill him, he spied a wooden hatch cover sitting loose on the deck nearby. The hatch would certainly float, and though it was no lifeboat, it would have to do. In the next couple of seconds he made his decision: “Finding no chance of mv life if I remained on board, and that I might as well be drowned as shot, I threw the hatch overboard, jumped after it.”

dead cargo: When pirates hope to find gold but instead discover sawdust, they call the object of disappointment dead cargo. “Barkeep! You call this rum?! I call it dead cargo!” or “Have you met Pirate Kate’s new swashbuckler? He’s indubitably dead cargo.”

dead man’s dinner / dying man’s dinner: A bit of food or drink taken when the ship is in extreme danger; any pause for refreshment before doing something unpleasant. “Well,’tis nearly time fer our weekly pirate’s progress meetin’. Shall we catch a bite o’ dead man’s dinner beforehand?”

deck: Platforms laid horizontally in a ship; in effect, the “floor” of the ship. The word also serves as a useful adjective preceding any number of generic insults:

“Shiver me timbers, ye deck-heap. Lift a limb and look lively!”; “You there! The swab with hair like a deck-mop.” (Please note that if you are an avuncular Scottish pirate, it can also be an expression of rough-knuckled affection. “Hoot mahn, ye wee deck monkey!”)

delve: To search earnestly, or to dig with a shovel. Useful also as a piratical alternative to “Don’t go there, girl!”; that is, “We dare not delve there, wench!”

derelict: Anything abandoned at sea, most often a ship. “Ain’t no one aboard, Cap’n–she’s a derelict.” Also, any faculty or ability fallen into disuse. “Bob’s powers of piracy have gone derelict since he took that job at the Hudson’s Bay Company” (See also dillywreck)

derring-do: Daring exploits in general. “What feats o’ piratical derring-do shall we git up to today, me hearties!”

devilry: Spirited roguery; that is, deliberate and vigorous mischief. “Me wooden leg replaced by a cucumber as I slept? What devilry is this?”

devil’s (anything): Pirates love to put the word devil’s in front of just about anything that they want to seem naughty, sinful or dangerous. For example, “devil’s books” are playing cards; “devil’s teeth” are dice; black and yellow are called the “devil’s colors”; and a menacing cloud bank is called the “devil’s tablecloth.”

dillywreck: Pirates who are missing teeth, deafened by cannon fire or merely lacking the power of enunciation say dillywreck when “derelict” is too much of a tongue twister. “Aye, ever since termites et the Cap’n’s leg, he just sets about like a dillywreck.”

dimsel: A body of stagnant water larger than a pond but not a lake. “Hoy! You with the dimsel breath. Ever tried garglin’ with creosote?” “No, dimsel-wit, I ain’t. Ever tried sayin’ ‘derelict’ with yer teeth knocked out?”

dine with Duke Humphrey: To go hungry. “As the devil is me witness, I thought gunpowder was edible. Guess we’ll all be dinin’ with Duke Humphrey tonight.” You may be wondering who Duke Humphrey was and why eating with him should leave people hungry. If so, furrow your brow and read on. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (1399-1447) was the youngest son of King Henry IV. Although Humphrey was buried in the graveyard of an English church called St. Alban’s, there was a statue or monument in his memory at a different church, Old St. Paul’s. Because of this, the walkway at St. Paul’s was called Duke Humphrey’s Walk, and it was a favourite spot for down-on-their-luck lackeys, ruffians and sea captains to go for a bit of a prom-enade. Since none of these sorts had any money to buy food, they were said to “dine” on the sight of all the different monuments and statues. And so dinin’ with Duke Humphrey came to mean “going hungry.”

dirty dog: An insult, often overused, but no less excellent for it.

“So, then, Bounder Bob promises to bent on a splice with Voluptuous Liz, swives her, then purloins her treasure map and runs off with Cheatin’ Charlotte!”

“What a dirty dog!”

ditty bag: A bag used at sea for personal possessions. “I like yer ditty bag, matey. ‘Tis a pretty one what with its bright colours and bold floral pattern.”

don’t let your antifreeze

A nonsense farewell in PEI, seemingly a punning take on “Don’t let your auntie freeze.

Don’t like the weather? Just wait five minutes

In Vancouver and Calgary, a rhetorical phrase reflecting the city’s fickle weather patterns, being capable of rain, snow and sunshine all within a few minutes of one another.

dooryard

An expression in Carleton County, New Brunswick, to delineate an outdoor area of the home not in use for farming, presumably a yard located just outside the back door. “You and your friends take your two-four out in the dooryard to drink it.”

double-double

When ordering coffee, to ask for two creams and two sugars. “One small black coffee, two medium regular and one large double-double.” In recent years this has become a famous Canadianism and has even been added to

The Canadian Oxford Dictionary. There are unconfirmed reports that U.S. soldiers serving in Afghanistan overheard their Canadian comrades requesting coffee this way (in Afghanistan’s only Tim Hortons) and thought they were speaking some sort of code. The Americans reportedly then invented their own slang “quadruple quadruple,” which is presumably equivalent to four by four (see also triple-triple).

doughnut vs. donut

The truth is that you’ll see both spellings on either side of the border, but Canadians lean somewhat towards “doughnut” when spelling out the name of this favourite snack, whereas Americans are more likely to spell it “donut.”

drain the main vein

To pee (generally used by men). “Whew! We’re halfway through that two-four. Time to drain the main vein.”

drash of rain

In PEI, 1) (noun) a heavy shower of rain. “We got soaked by a drash of rain.” 2) (verb) of the sea or rough lake water, to splash violently and soakingly. “The waves drashed all over them.”

dream in Technicolor To be wildly unrealistic.

“Have you heard Jen’s latest plans? After she becomes a private detective, she’s gonna manage a Latin jazz troupe and then open an arctic orchid sanctuary.”

“She’s dreamin’ in Technicolor.” (Note: Sticklers for Canadian spelling should note that, since it is a trademarked name,

“Technicolor” cannot be spelled “Technicolour.”)

CHAPTER FOUR

The Spectral Lights of Cornwall

Investigating a haunting that occurred more than 150 years ago is difficult enough, but searching for clues when the haunted house is under several metres of water presents another level of difficulty altogether. With the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway in the 1950s, many small settlements were inundated “full fathom five,” as Shakespeare put it. Among these was the homestead known in the 19th century as Marsh’s Point on the outskirts of a thriving little community called Milles-Roches.

Until the 1830s, Milles-Roches was located on a large headland that stuck out into the St. Lawrence River. But starting in 1834, with the construction of the Cornwall Canal, the village was transformed into an island by the new waterway that separated it from the mainland by several metres. Milles-Roches was now inaccessible except via a dripping underwater tunnel that connected it to the mainland. The canal also severed Marsh’s Point from the mainland, as well as from Milles-Roches. It was now an island that could only be reached through the subaqueous passage known as the “Milles-Roches culvert.”

The house on Marsh’s Point had been built decades earlier in a picturesque little grove of hickory trees. It had a pointed roof with steep, sloping sides, and its solitary placement on its own small island gave it a still, ghostly air. The house’s occupants were Clara Marsh, aged 60, and her mother, 80, who was only ever referred to as “Granny” Marsh. The women rarely left their house except when they braved the seeping tunnel to go into town for supplies.

One night, in the autumn of 1845, a farmer was walking along the edge of the canal on the mainland side. He happened to look toward Marsh’s Point and was surprised to see a number of moving lights near the house, as though several people were carrying lanterns about. He assumed that the Marsh women were either gravely ill or injured or had some other misfortune befall them that required help from the neighbours. The next morning, the farmer called at the house to express his sympathy or condolences, whichever might be required. Imagine his surprise when he found that both Granny and Clara Marsh were fine, and furthermore, that they had no idea a party of lantern bearers had been swarming around their house the night before in fact, the notion quite amused them. Sightings of the ghostly lights continued, with more and more people seeing them until finally all of the Marshes’ neighbours had, at one time or another, been witness to the strange illuminations that floated around the old farmhouse.

After the Marsh women themselves finally saw the lights, they asked nearby farming families to keep watch on their property for any strange “doings.” The inhabitants of the entire countryside rose to the occasion, all eager to solve the mystery. The watchers organized themselves into pairs and set up nightly patrols on Marsh’s Point, vigilantly peering into the darkness as the two women slept inside the house. One of most puzzling aspects of the whole affair was that observers on the mainland often saw things happening near the house that the night watchers who were actually at the house were completely unaware of. One night, people keeping watch from the far side of the canal swore they saw a red-hot stove in front of the house, with several figures carrying pans of bread back and forth between the glowing oven and the surrounding darkness. But the Marsh’s Point watchers who were on the property that night said they hadn’t seen anything of the sort, neither phantom oven nor spectral bakers. Subsequent inquiries showed that no oven or stove matching the one observed could be found anywhere in the house or on the property.

However, people in the house and on the immediate property also reported strange goings-on. The Marshes began to hear strange sounds in the disused sections of the rambling old house. Although the so-called ghosts never invaded Granny and Clara’s actual living quarters, loud noises began to emanate from the darkened rooms and passages that the Marsh family had occupied during the house’s heyday. The two women were quite frightened but could not be persuaded to leave. Eventually, they appear to have simply grown used to the noisy disturbances, which did them no harm besides startling them out of their slumbers.

By far, the most frequently seen and most baffling phenomenon was the ongoing presence of large numbers of floating lights. Sometimes visible only from the mainland, but other times also quite apparent from the house, the dancing lights tended to appear in groups. On one occasion, the lights appeared to gather themselves into an enormous formation over the house, swinging back and forth in a straight line, like a pendulum describing an arc. Another time, they were seen to run along the ground in a line until they reached a tree, whereupon the lights climbed the trunk and scattered prettily among the branches, apparently playing hide and seek, like so many fireflies. Sometimes the lights’ movements seemed random and rather playful, while at other times they appeared to show purpose and deliberation.

One night, as observers looked on from the mainland, a cluster of lights gathered on the Marsh’s Point side by the water of the canal. There they hovered, except for one of their number that struck out across the canal, very close to the surface of the water. To the amazement of the onlookers, the single light sped across the water until it reached the other side of the canal some distance away, then shot up into the branches of an immense tree and seemed to dart around as though looking about from this high vantage point. Next, the light descended, crossed the canal again and appeared to be welcomed back to Marsh’s Point by its waiting companions, which clustered around the light as though wanting to hear of any news or perhaps congratulate it on its bravery.

THE PLAINS OF ABRAHAM

September 13, 2009, was the 250th anniversary of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, now widely considered to have been the death stroke for French rule in Canada. For the anniversary there had been plans to stage a re-enactment, but there were storms of protest and threats of civil disobedience from Québécers tired of being reminded that their province is still a part of Canada. And so the re-enactment was called off, but what might have happened if it had taken place?

RON: Hello to everyone here and all the viewers at home. Welcome to the 250th anniversary re-enactment of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.

DON: There’s nobody here, Ron, and there’s nobody watching at home.

RON: Well, I’m sure that somebody’s watching-

DON: No, Ron, nobody’s watching, and do you know why nobody’s watching? Because the stupid producers decided to stage this thing in real time. It’s two o’clock in the morning right now and the British are still anchored upstream just getting ready to cast off. People get up at two o’clock in the morning to watch the Olympics, Ron, not to watch a bunch of Little Lord Fauntleroys run around in pretty jackets and shoot blanks at each other. There’s nothing going on, and even if there was, it’s pitch black and we can’t see anything.

RON: Well, how about that gunfire I can hear? That’s something.

DON: Yeah, it’s a diversionary bombardment that the British are staging farther upriver, and they’ve been doing it all night and it’s starting to drive me crazy. How am I supposed to get any sleep?

RON: Ah, but that diversionary bombardment worked, didn’t it, Don? It made the French general, Montcalm, believe that the attack would come elsewhere.

DON: Ron, the British could have farted into the wind and the French would have thought the attack was going to be somewhere else, because the idea of attacking a location where you have to get your troops to climb up 150 feet of steep cliff-side in the pitch dark is completely insane.

RON: But that’s just what General Wolfe did.

DON: Sadly, it’s the very reason we’re here right now – at two o’clock in the morning.

RON: Five after two now actually. Don, since we’ve got a bit of time until they drop the puck–I mean, until they start the fight–maybe you could give us some background.

DON: Aw, whatever – it’s the Seven Years’ War – blah blah blah – the French have been kicking English ass pretty good, but you know how I feel about the French, Ron.

RON: I sure do, Don. Now, as I understand it, General Wolfe’s forces have recently been trounced in their attack on Montmorency.

DON: If this was a seven-game series, the French would be leading three to two.

RON: Tell us a bit about the players.

DON: Well, of course, the two enforcers are Montcalm for the French, and Wolfe for the British.

RON: Let’s start with Montcalm.

DON: Well, he’s French, Ron, and you know how I feel about the French.

RON: I sure do, Don.

DON: Actually, Montcalm is an OK general, but he just doesn’t seal the deal.

RON: You’re referring to his habit of fighting the British off but not actually going after them even when he has them on the run?

DON: Yeah, it’s like he can get the puck out of his end zone, but he just doesn’t take any shots on the other team’s net.